TL;DR / Key Takeaways

- KISS: Prefer explicit, straightforward code over clever abstractions and meta‑frameworks.

- DRY: Extract duplication when it stabilizes (2–3 occurrences), co‑locate by domain, avoid over‑DRY generalizations.

- YAGNI: Build for today’s needs; capture future ideas in the backlog, not in code. Keep adding later cheaply via tests.

- Balance with a simple heuristic: cost to add later, duplication threshold, domain volatility, and team familiarity.

- The post includes practical before/after examples and small code snippets in Python, TypeScript, and Go.

Introduction

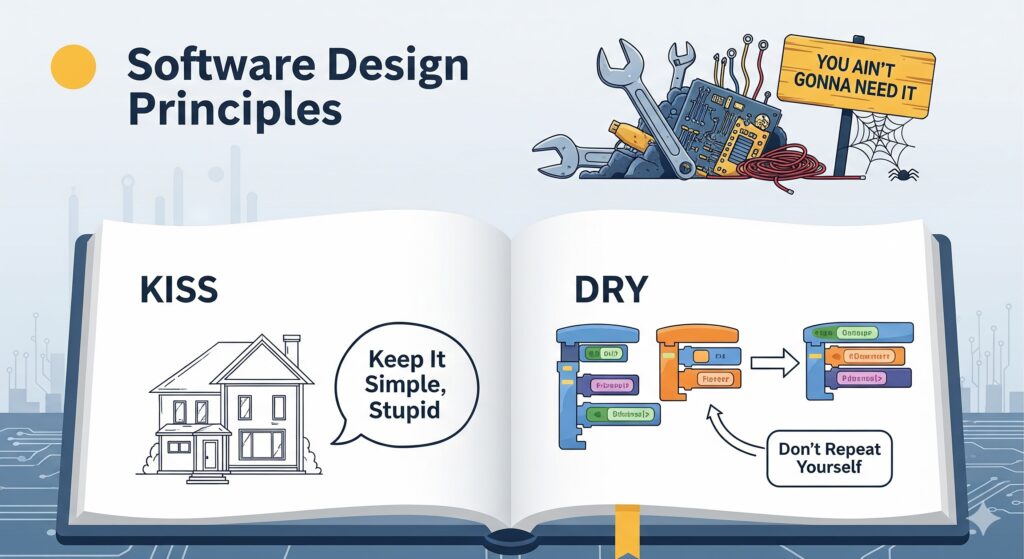

If you’ve ever stared at a codebase and thought, “Why is this so complicated?” you’re not alone. Most of the time, complexity isn’t malicious—it sneaks in through “just in case” features, copy‑pasted fixes, and clever abstractions that outgrow their usefulness. Three simple guardrails help keep us honest: KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid), DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself), and YAGNI (You Aren’t Gonna Need It).

This post takes a practical tour through these principles with examples you can apply today. We’ll look at when each principle shines, when it backfires, and how to balance simplicity with extensibility on real teams.

Background: Why These Principles Still Matter

Modern systems spread across services, queues, and clouds. The more moving parts, the harder it is to change anything safely. KISS, DRY, and YAGNI counter that drift:

- KISS: Optimize for clarity first; cleverness later (if ever).

- DRY: Consolidate knowledge so one change fixes everything it affects.

- YAGNI: Resist building for hypothetical futures until real requirements arrive.

Used together, they protect maintainability, keep delivery fast, and reduce risk.

Deep Dive: Putting KISS, DRY, and YAGNI to Work

KISS: Small, Obvious, and Boring (On Purpose)

KISS is about removing unnecessary complexity. Prefer straightforward logic, fewer concepts, and minimal configuration.

Example: Replace clever “generic” plumbing with plain, intention‑revealing code.

# ❌ Too clever: over-generalized pipeline

class Step:

def run(self, input):

raise NotImplementedError

class Pipeline:

def __init__(self, steps):

self.steps = steps

def execute(self, value):

for s in self.steps:

value = s.run(value)

return value

# ... plus 6 different Step subclasses to validate, transform, store, and notify

# ✅ KISS: read-then-validate-then-save, clearly

def register_user(user_data, repository, notifier):

if not is_valid_email(user_data.get("email")):

raise ValueError("Invalid email")

user = repository.create(user_data)

notifier.send_welcome(user.email)

return user

def is_valid_email(email: str) -> bool:

return isinstance(email, str) and "@" in email

Guidelines for KISS:

- Prefer two functions over one meta‑framework.

- Hide complexity behind small names only when it actually reduces mental load.

- Default to conventional patterns your team already knows.

When KISS can be misread: KISS isn’t “never abstract.” It’s “don’t abstract prematurely.” If complexity is inherent (e.g., payment flows), model it explicitly, not with magic.

DRY: Don’t Repeat Knowledge (Not Just Code)

DRY eliminates duplication of intent. Duplicate logic drifts; one copy gets patched, and the other becomes a bug farm.

Typical DRY violations:

- Copy‑pasted validation rules across services

- Business formulas are reproduced in multiple jobs

- Repeated API request wrappers with slight variations

Refactor pattern: extract shared behavior behind a simple interface—without creating a “God util.”

// ❌ Repeated validation in two routes

function validateEmail(email: string) {

return /.+@.+\..+/.test(email);

}

// POST /register

if (!validateEmail(req.body.email)) {

return res.status(400).send("Invalid email");

}

// POST /invite

if (!validateEmail(req.body.email)) { // duplicated rule

return res.status(400).send("Invalid email");

}

// ✅ DRY: shared validation with intent-revealing name

export function assertEmail(value: unknown): string {

if (typeof value !== "string" || !/.+@.+\..+/.test(value)) {

throw new Error("Invalid email");

}

return value;

}

// Usage

const email = assertEmail(req.body.email);

Practical DRY safeguards:

- Duplicate once? Fine. Duplicate twice? Extract.

- Co‑locate shared code near its domain; avoid dumping everything into

utils/. - Write tests around the single source of truth so changes are deliberate.

Over‑DRYing warning: If your abstraction requires special‑case flags (isForInvite=true) or complex branching, you may be hiding different concepts. Split them.

YAGNI: Ship What’s Needed—Nothing More

YAGNI is a counterweight to speculative architecture. Build the smallest thing that satisfies today’s requirement; keep it easy to extend tomorrow.

Symptoms of YAGNI violations:

- Feature flags for features no one asked for

- Extensible plugin frameworks for a single implementation

- Overly generic data models that complicate simple queries

Example: Remove speculative parameters and reduce scope.

// ❌ Premature flexibility: unused options and callbacks

type SaveOptions struct {

Retry int

OnSuccess func(id string)

OnFailure func(err error)

}

func SaveOrder(o Order, opts *SaveOptions) (string, error) {

// complex branching to honor options ...

}

// ✅ YAGNI: keep API small; add options when you actually need them

func SaveOrder(o Order) (string, error) {

id, err := repository.Create(o)

return id, err

}

YAGNI in agile teams:

- Capture “maybe later” ideas as backlog items, not code.

- Timebox experiments behind feature branches or toggles; delete if the value isn’t proven.

- Write change‑friendly code (clear seams, tests), so adding later is cheap.

Balancing the Trio: A Simple Decision Heuristic

When choosing between “simple now” and “general later,” use this quick check:

- Cost to add later: Low? Prefer KISS + YAGNI.

- Similar code appears in 3 places: Extract (DRY), but review when divergence appears.

- Domain is volatile: Keep code straightforward; let patterns emerge from usage.

- Domain is stable and shared: Introduce a well‑named abstraction with tests.

Think in gradients, not absolutes. KISS, DRY, and YAGNI are levers, not laws.

Real‑World Scenarios: Before and After

1) Over‑abstracted module turned simple orchestrator

- Before: A “workflow engine” with JSON‑defined steps for a three‑step signup. Each new step required custom adapters and mapping code.

- After: A small orchestrator function calls the domain services in order. Less config, fewer moving parts, same outcome. Lead time dropped because changes were code‑reviewed functions, not framework wiring.

2) Duplicated calculations harmonized under DRY

- Before: Discount calculation existed in checkout, admin reports, and a nightly job—with different rounding rules. Bugs surfaced randomly.

- After: A single

DiscountPolicywith explicit rule versions and tests. Reports, jobs, and checkout import and call it. One fix, everywhere.

3) YAGNI for integrations

- Before: A pluggable “PaymentProvider” layer with adapters for providers the product didn’t use.

- After: A thin

Paymentsservice for the single provider in production, with clear seams to add a second provider when needed.

Measuring Design Simplicity (Signals, Not Scores)

Use lightweight signals to catch complexity early:

- Change surface: A small fix shouldn’t touch many files.

- Cognitive load: Can a new teammate explain a module after 10 minutes?

- Cyclomatic/cognitive complexity: Track hot functions; refactor the top offenders.

- Test shape: Are tests unit‑level and fast, or only possible end‑to‑end?

- Diff size: Do trivial changes create large refactors? That’s a smell.

These signals guide conversations; avoid chasing metrics for their own sake.

Team Tactics That Make These Principles Stick

- Definition of Done: Include “kept it simple,” “no unnecessary options,” and “consolidated duplication.”

- ADRs (lightweight): When introducing an abstraction, add a short Architecture Decision Record explaining why it pulls its weight.

- Code review prompts: “Is this the simplest thing?”, “Are we repeating knowledge?”, “What if we don’t build this yet?”

- Delete with pride: Removing unused code is shipping value.

Quick Reference Cheatsheet

- KISS: Prefer explicit code over frameworks and flags. Optimize for reading.

- DRY: Extract only when duplication stabilizes; co‑locate by domain.

- YAGNI: Log future ideas; implement when real needs arrive.

- All three: Make later changes cheaply through tests.

Conclusion

Great software isn’t just powerful—it’s approachable. KISS keeps the path clear, DRY keeps knowledge consistent, and YAGNI keeps scope honest. When you apply them together with judgment, you get systems that are faster to change, easier to reason about, and friendlier for the next developer (which is usually future you).

Ship the simplest thing that works. Extract duplication when it hurts. Add flexibility when reality—not imagination—demands it.

This article is part of the Software Architecture Mastery Series. Next: “Separation of Concerns: From Theory to Implementation”