TL;DR / Key Takeaways

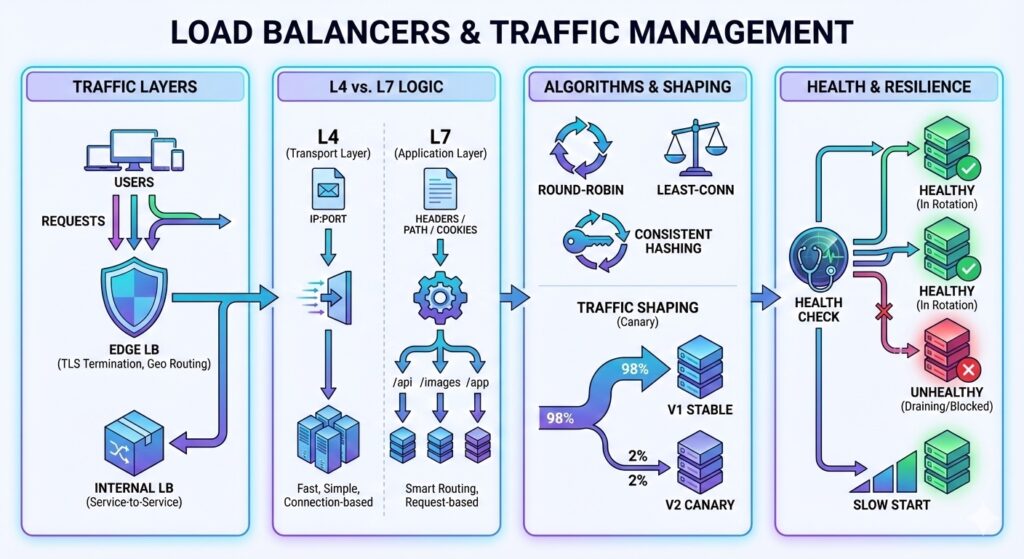

- Load balancers – L4 balances connections; L7 balances requests and can route by content.

- Algorithms trade simplicity for fairness: round-robin, least-connections, and hashing.

- Health checks and slow-start prevent sending traffic to bad or cold nodes.

- Global load balancing trades latency for availability across regions.

Why Load Balancers Matter

They turn many unreliable servers into one reliable service. A good load balancer hides failures, spreads load, and enables horizontal scaling.

L4 vs L7 in Simple Terms

- L4 (transport): routes based on IP and port. Fast and simple.

- L7 (application): routes based on headers, paths, or user attributes. More control, more cost.

Use L4 when you only need even traffic. Use L7 when you need smart routing.

Where Load Balancers Sit

Most systems use multiple layers:

- Edge load balancer: terminates TLS, enforces rate limits, and routes by region.

- Internal load balancer: balances service-to-service traffic within a region.

TLS termination at the edge reduces CPU cost on services, but you must secure internal traffic with mutual TLS (mTLS) or a trusted network boundary.

Routing Algorithms

- Round-robin: simplest, assumes all nodes are equal.

- Least-connections: better when request cost varies.

- Consistent hashing: keeps session or cache affinity stable.

Traffic Shaping and Progressive Delivery

Modern load balancers do more than balance:

- Weighted routing for canary (small percent of traffic) or blue-green (two full stacks with a switch) deployments.

- Header or cookie routing to isolate test traffic.

- Geo routing to keep data residency requirements.

These features reduce risk but add configuration complexity and require good observability.

Health Checks and Slow Start

Health checks keep bad nodes out of rotation. Slow start prevents a newly added node from being flooded before its caches are warm.

sequenceDiagram User->>LB: Request LB->>ServiceA: Route ServiceA-->>LB: Response LB-->>User: Response

Health Check Details

- Active checks probe an endpoint; passive checks watch for errors.

- Use thresholds (for example 3 consecutive failures) to avoid flapping.

- Drain connections before removing a node to avoid dropping in-flight requests.

Worked Example: Canary and Health Check Timing

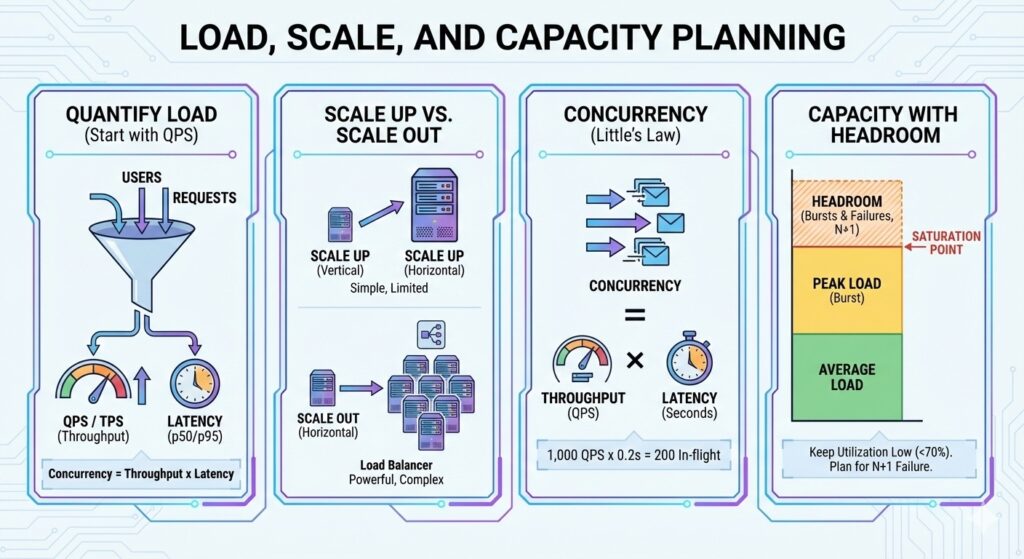

Assume 120,000 RPS total traffic and a 2 percent canary weight.

- Canary traffic = 120,000 * 0.02 = 2,400 RPS

For health checks, assume a 5 second interval and 3 consecutive failures:

- Detection time = 5 * 3 = 15 seconds

- With a 10 second drain, total time to stop traffic is about 25 seconds

Session Affinity and State

Sticky sessions help stateful services but reduce load balancing quality.

If you need affinity, prefer stateless designs with shared stores or short-lived session tokens.

Global vs Regional Load Balancing

- Regional: low latency, simple data residency, fewer failure domains.

- Global: routes users to the nearest region and survives regional outages.

Global routing adds latency for cross-region data access and consistency.

Failure Modes to Watch

- Health check flapping causes traffic thrash.

- Uneven load sends heavy requests to the same node.

- Sticky sessions reduce effective load balancing and raise tail latency.

- Load balancer becomes a single point of failure if not redundant.

Interview Framing

When asked about load balancing, explain:

- Which layer you would use and why.

- The routing algorithm and its trade-offs.

- How you detect and drain failing nodes.

Checklist

- Pick L4 or L7 based on routing needs.

- Choose a routing algorithm and explain the trade-off.

- Add health checks and slow start.

- Plan for redundancy at the load balancer layer.